Inflation Series (Part 3)

Will the 2020s US end up like 1920s Germany?

Weimar Republic (German Government Regime Post World War I, 1918-1933)

In two previous articles we explored the basics around inflation (what it is composed of, what drives it, etc.) and then examined whether the United States might ultimately parallel the low inflation environment Japan has experienced for the last thirty years. We concluded that there are significant policy and cultural differences between the US and Japan and thus it is unlikely the US will follow in the deflationary footsteps of Japan.

Given this, is it possible the US way overshoots on its inflation targets? Could policy makers lose control and could sheer indifference allow for “higher for longer” inflation, or even hyperinflation as seen during Germany’s Weimar Republic regime?

While Weimar Germany after World War I is hardly the only instance of hyperinflation in history, we are focusing on it because some prominent financial minds like Michael Bury have directly compared the current United States to Weimar Germany. In theory, it is a logical example to point to given Weimar Germany was one of the only recent, modernized economies to go through hyperinflation, as opposed to more common cases in emerging economies. Bury’s argument is that Germany from 1914-1923 is similar to the United States from the financial crisis up until now:

“Throughout these years the structure itself was quietly building itself up for the blow…Germany’s #inflationcycle ran not for a year but for nine years, representing eight years of gestation and only one year of collapse.”

While lacking any specific empirical evidence, (at least any shared via Twitter) Bury points to several parallels, noting that:

“One was the great wealth, at least of those favored by the boom…business and stock market were booming…side by side with the wealth were the pockets of poverty. Greater numbers of people remained on the outside of the easy money, looking in but unable to enter. The crime rate soared…demoralization…crept over the common people…from watching their own precarious positions slip while others grew so conspicuously rich…almost any kind of business could make money…the boom suspended the normal processes of natural selection…speculation alone, while adding nothing to Germany’s wealth, became one of its largest activities…everyone from the elevator [operator] up was playing the market.”

To paraphrase as best we can, Bury is arguing that 9-10 years of easy money policies has been the “gestation” period of the US economy, where waves of speculation have been building, weird types of businesses and investments are occurring (see here and here for corollaries), and wealth disparity/crime is increasing. The ultimate upshot is that there will be an eventual crisis of confidence in our currency, which tends to be the driving force behind all hyperinflation, and that policy makers will lose control of their purported tools to manage inflation.

Germany’s Hyperinflation

From 1922 -1923, Germany went through one of the worst periods of inflation that a modern, industrialized nation has ever seen. By November of 1923 one US dollar was worth 4.21 trillion German marks.1

The roots of this inflation started with the Great War itself, which demanded incredible fundraising from all countries participating, France, Germany, and Britain most notably. Countries had various strategies for this fundraising, but most centered on aggressively borrowing and raising taxes with the thinking being that the war would not last very long and these would be temporary measures. John Maynard Keynes, in one of his fallacious predictions, noted he was “quite certain the war could not last more than a year.”2

On the contrary, the War lasted for more than four years, from 1914 to November 1918, with the Treaty of Versailles being signed in June of 1919. During that time, Britain is estimated to have spent $43 billion, France $30 billion, and Germany $47 billion (multiply this by ~13x for figures in today’s values), while their total currency in circulation rose 2x, 3x, and 4x, respectively.3 While one can draw parallels here with large increases in the money supply to the United States, it should be noted that unlike the United States now, inflation in Germany during the War exceeded 40% a year.4 To this point, we find Bury’s argument that there was a 9-year benign gestation period followed by massive hyperinflation to be misleading. In fact, there was extraordinary volatility in prices throughout the war and thereafter, ultimately resulting in the crescendo of hyperinflation.

Intentional Hyperinflation Due to Reparations?

When thinking about differences between the US now and Germany in 1922, one can immediately point to the draconian reparation payments Germany was sentenced to pay. Indeed, as Adam Ferguson, the author of “Dying of Money” notes, the “ask” from the Allies was quite stupendous:

“The allies first firm bill for reparations, presented in May of 1921, amounted to the fantastic sum of 132 billion gold marks. This was about four times Germany’s maximum annual national product and greater even than Germany’s entire national wealth; it was like asking the United States in 1973 to pay more than four trillion dollars in gold over a period of years.”

Looking at this, one could logically conclude that the Germans knew they were basically screwed and went down the intentional path of hyperinflation to clear their debts. However, the differences between the demands (132 billion gold marks) and what ended up being paid between the end of the War and hyperinflation period (2.4 billion gold marks) was gigantic. This 2.4 billion marks amounted to about five percent of a year’s national product.

Ferguson comes to the same conclusion:

“That Germany inflated deliberately in order to avoid the costs of reparations is not a proposition that bears examination. The evidence is wholly against it. First, the rate of inflation was enormous long before reparations was an issue. Second, industrial pressure to inflate, largely self-interested, had nothing directly to do with the war debt. Third, it was correctly recognized that…reparations had to be paid either in kind or in gold equivalents…fourth, at no time did Germany’s financial authorities so much as hint, privately or publicly, that their policies derived from cynicism rather than incomprehension and incapacity.”

To summarize, inflation in Germany existed before the reparations bill, many people liked the inflation, reparation receiving countries demanded non-inflated payments, and the German authorities appeared more inept than Machiavellian.

Reparations as an Indirect Cause of Hyperinflation

If reparations did not directly create hyperinflation could they have indirectly contributed? The evidence here is far greater and convincing and the crisis of confidence in the mark can be at least partly attributed to the reparational Sword of Damocles hanging over Germany.

We would argue that the reparation demands were but the opening of a series of catalysts that ultimately led to hyperinflation. A vicious cycle occurred in Germany following the reparations bill whereby Germany implemented a series of higher taxes to pay the debt which in turn created the ever present threat of even more/higher taxes coming at any moment. This rise in taxes and anticipation of more was followed by widespread demand for higher wages, with the only realistic option of raising wages being done through inflationary mechanisms. This aggressive taxing and “medicine taking” may have actually worked to pay off a good chunk of the reparations if there existed the political will to resist the unions and industrialists who argued that both higher wages and inflation were not just necessary, but a good thing:

“The mighty Stinnes Group, for one, was still working on gold capital. The fall in the value of the paper mark, however, had written off 98 percent of the gold debt…Hugo Stinnes himself, the richest and most powerful industrialist in Germany, whose empire of over one-sixth of the country’s industry had been largely built on the advantageous foundation of an inflationary economy, paraded a social conscience shamelessly. He justified inflation as a means of guaranteeing full employment, not as something desirable but simply the only course open to a benevolent government.”

In addition to inflating away paper mark debt, those industries primarily involved in exporting also now had a strategic advantage with a severely devalued local currency.

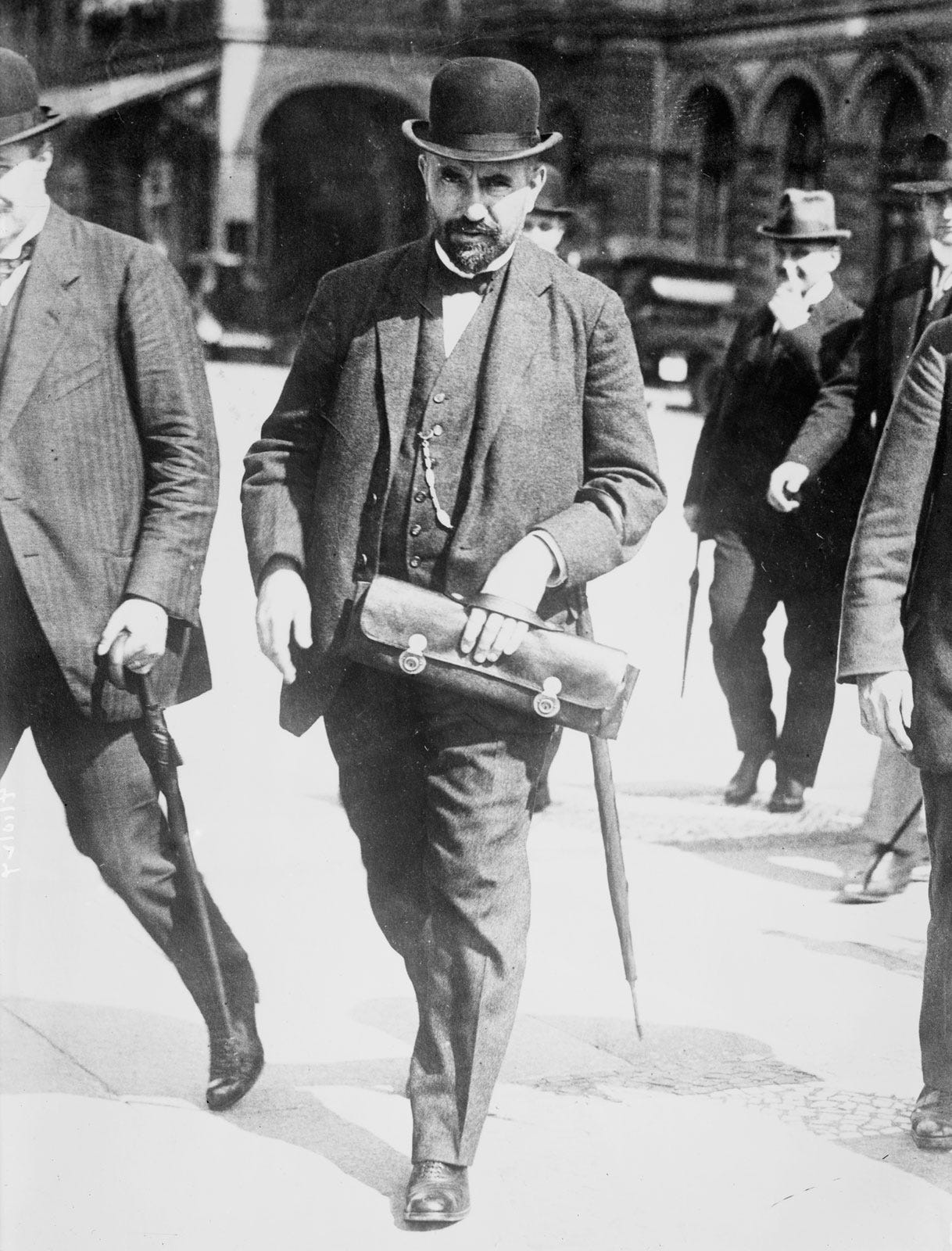

A major psychological blow was later dealt with regard to the Minister of Finance, Matthias Erzberger. Erzberger was the one who signed the armistice on behalf of Germany in 1918. While this caused many Germans to view him as a traitor, internationally Erzberger was viewed as the responsible one who would take the reparations payments seriously. The series of taxes and reforms proposed by Erzberger to help pay for the reparations caused his political opponents to hurl a brushback pitch at him by linking him publicly to a corruption scandal. Public pressure led to his subsequent resignation which “may be taken as Germany’s turning point, from this day her crusader for financial probity was gone.”5 and after one unsuccessful attempt in 1920, Erzberger was assassinated in August 1921.

With Erzberger gone and industrialists like Stinnes and Fritz Thyssen heavily influencing policy under the new Minister of Finance and “chief architect of Germany’s economic disaster”, Karl Helfferich, there was no longer a perceived will for the Germans to act responsibly.

Indeed, because unemployment remained low and industry was booming, it was hard to find the political will to curb the rising inflation:

“Stopping the inflation would have killed the boom, and that seemed excessively unpleasant. In this respect, peacetime inflation was far more insidious than wartime inflation, which produced only war goods to be expended and no boom for the people to become addicted to…every day that passed, appeasing the inflationary dragon with more inflation, increased the assured severity of the inevitable medicine. So long as the Siren-like lure of the easy wealth continued, it was impossible to persuade enough of the nation that titanic measures of austerity…were necessary.”

It should be noted that basically all countries except Germany went through lengthy recessions after World War I, and it certainly could be argued that the longer the “boom” went on the greater the repercussions ultimately were.

A final but important point was the apparent naivety of Germany’s monetary policy makers to basic economic concepts. As Ferguson notes, “they staunchly denied that higher discount rates would moderate the inflation and on the contrary, opined that they would merely raise the costs of production and push up prices further.”

US as the Next Weimar?

It is now clear to us that no one factor led to hyperinflation in Germany, but rather the causal nexus was a series of factors in concert that self-reinforced each other, with the largest ones being:

Psychological crisis in confidence of the mark because of the draconian reparations demands

Erzberger assassination

Lack of will to curb inflation by influential political parties

Poor understanding and implementation of monetary policy

If we take all this together, we can certainly see some similarities between the US and Weimar and if pressed we could craft a narrative around very high inflation in the future.

One could argue that the United States is becoming more and more numb to responsible spending and that we are mortgaging our future by running up extravagant deficits in concert with ongoing quantitative easing. The monetary bases have expanded significantly, like Germany, with a Federal Reserve openly stating they are willing to “run hot”, and there is evidence of rising wealth disparity and rising crime in 2H 2020/1H 2021.

Furthermore, many of the current proposals from the US government, if actually implemented, could cause a surge of inflation. For instance, getting more aggressive on curbing carbon emissions is likely inflationary, as not only will there be government stimulus spending on renewable programs but actively shutting down cheaper energies sources will likely result in higher energy prices. The concept of a Universal Basic Income (a preview of which was seen during COVID, now potentially leading to a major worker shortage and wage inflation), could be quite inflationary, especially if it’s funded through debt. Another proposal being advanced by US Representative Maxine Waters is for a $25,000 down payment assistance program for homebuyers. With residential real estate price appreciation setting records in 2021, more down payment assistance and subsidies will only exacerbate housing affordability issues and not treat the root cause of lack of available supply. A lack of supply which also usually comes about due to local government regulations on issues such as minimum lot sizes and restrictive zoning.

Basically, there seems to be a lot of discussion around spending a lot of money, and not a lot of discussion around balancing a budget.

Our conclusion on this, however, is that unless you buy into the paranoid idea that the United States government wants hyperinflation as some kind of “reset” to their debt levels, it’s very unlikely that anything near hyperinflation would occur in the United States at the present or in the near future. We think there would be significant pushback from the Boomer generation whose savings would be destroyed. This is what occurred in Germany as the lower class who had no savings fared better than the middle class whose savings were wiped out.

Also the psychology today is largely different. For one thing, the United States does not have other countries pointing a gun to their head asking for reparations. While the United States does owe a lot of money to China and other countries, most of our federal debt is actually held by the Federal Reserve. And while many may hate to admit it, comparing the Federal Reserve’s understanding and skillset to Germany’s leaders in the 1920s is stark and quite favorable to the Fed.

In summary, while there are some similarities to post-WWI Germany in the current backdrop, we would argue there are critical differences that make hyperinflation very unlikely.

That does not mean we will not see sustained, elevated inflation though due to the ongoing money printing, along with some risks of stagnant growth due to supply constraints and the threat of higher taxes. At some point, the United States will have to face up to the fact that we have run up huge debt levels and vastly increased the monetary supply to “keep things going” for political expediency. But we are likely nowhere near that point, as Japan has demonstrated that debt/GDP levels can theoretically increase and be sustained well beyond where the US is today.

Western Civilizations, page 918

Lords of Finance, page 74

Lords of Finance, page 87

Lords of Finance, page 88

When Money Dies