Inflation Investigation (Part 2)

Why the US (Probably) Isn't the Next Japan

Having looked at the basics of inflation in the previous article in this series, we now turn to potential comparisons for the United States’ present situation, starting with Japan. Japan is often brought up as a “preview” of what’s to come for the United States and Europe given their low interest rates and aging demographic base.

To set the stage for the basis of this comparison, it is important to understand that Japan had a massive asset bubble in the 1980s which we wrote about here. The historic bubble was characterized by low interest rates, an increased marketability of assets, excessive money printing, and a nationwide speculative euphoria. (Sound familiar?)

The easy credit provided by both banks and shadow banks during the 1980s resulted in an overly leveraged corporate and consumer sector (similar to the US in 2008-2009). During that time, everything from contemporary paintings to country club memberships could be used as collateral to fund real estate and stock speculation. This self-perpetuating relationship drove the bubble on the way up and made the unwind equally severe on the way down:

“When the bubble burst, commercial real estate prices fell 87% nationally, touching levels last seen in 1973…since real estate was always used as collateral for borrowing money in Japan, the collapse of land prices devastated private-sector balance sheets."1

That’s right, commercial real estate prices dropped 87%! For reference, the US housing market fell about 33% during the Great Recession in 2008.

By 1991, 38% of 12 trillion yen in loans (~$110 billion USD today) from "shadow banks" were non-performing and by 1995 a full 75% of these loans were non-performing. The government stepped in with bailouts equivalent to ~11% of Japan's GDP at the time to cover bad debts.

Lost Decades(s): 1990 - Present

Since the bubble popped in 1990, Japan has been mired in 30 years of stagnant growth characterized by low inflation (at times deflation), high savings rates, and low loan growth. The original “lost decade” from 1990 – 2000 has now turned into three lost decades.

Since that time, the United States has routinely had around 2% a year higher inflation than Japan:

The stagnancy has remained despite aggressive quantitative easing by the Bank of Japan who has expanded the money supply by over 16x since 1990. As can be seen below, there seems to be a severe diminishing return for what expanding the monetary base can do in terms of stimulating lending (and in turn GDP/inflation). There are those like Ken Fisher who believe that QE can actually be deflationary because it inevitability results in a flattened yield curve, which disincentivizes banks to lend.

There has been debate about whether the general economic sluggishness in Japan is 1) primarily psychological, 2) a function of changing demographics, or 3) a rational, mechanical response to repair balance sheets that has never fully been completed.

We believe the work of Richard Koo, Chief Economist at the Nomura Research Institute, who has studied Japan as well as other recessions/depressions, has merit as a potential analytical framework.

Koo has made his career arguing that traditional macroeconomic analysis has a major blind spot. The traditional view is that monetary policy can impact inflation in all circumstances. The argument goes that because the central bank can effectively manipulate interest rates, there will always be demand for loans if rates go low enough, with loan generation leading to growth, improving money velocity, and ultimately inflation. The key underpinning of this theory is that companies and people are rational economic actors who will always try to maximize profits.

Koo, however, believes this is only true when an economy is not in what he calls a "balance sheet recession." During a period like this people and corporations will go into a mode of "debt minimization" rather than profit maximization, under which no level of interest rates will convince them to take on more debt. When countries are in this state of debt minimization, quantitative easing as a monetary policy becomes ineffective.

"‘Inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon' may be valid when there is strong private-sector demand for funds but is basically irrelevant when the private sector refuses to borrow despite zero or even negative interest rates." – Richard Koo, “The Other Side of Macroeconomics”2

Koo’s Prescription

Koo argues that to break out of a “balance sheet recession” countries need to engage in sustained, aggressive fiscal stimulus, meaning the government needs to be the borrower of last resort with the government then spending that money. To this point, he recommends stimulus comes in the forms of infrastructure projects as opposed to tax cuts because while tax cuts do help repair balance sheets, they don’t directly encourage spending. Also, in order to generate reasonable inflation and get out of a potential deflationary spiral, this policy needs to be sustained and cannot be curtailed at the first sign of recovery.

"Experience shows that when private-sector borrowers disappear, fiscal stimulus is absolutely essential in keeping the economy going. Every time fiscal stimulus was implemented, the economy improved, and every time it was removed, the economy collapsed."3

In his book the “The Other Side of Macroeconomics”, Koo is quite critical of Japanese and European policy where he believes “fiscal hawks” rein in stimulus at the first sign of recovery. This leads to a relapse into low growth before balance sheets has been fully repaired.

He notes that Japan “did the right thing” from 1990-1997 and the situation would have been measurably worse without the large stimulative fiscal policies that amounted to 11% of Japan’s GDP at the time. While the bursting of the bubble in 1990 caused wealth losses that exceeded losses during the Great Depression, nominal GDP in Japan never dropped below bubble highs and unemployment never went above 5.5%. In other words, the stimulus worked as intended and the government initially avoided a painful recession.

However, in 1997 fiscal austerity measures were put into place too early which Koo estimates set the country back a full decade. In 1998 GDP dropped 1.1% while the national deficit expanded by 72%...not a great combination.

The US Today

To the point of this article, Koo believes the US generally “gets it”, with high praise in particular for Ben Bernanke:

"He understood that when the private sector is not borrowing money, the effectiveness of monetary policy is dependent on the last borrower standing, i.e., the government. Even though the US came close to falling off the fiscal cliff on several occasions, it is doing better now because, after eight years of fiscal support, private-sector balance sheets are growing healthier, and some households are actually starting to borrow again."- ‘The Other Side of Macroeconomics’

We would argue that based on Koo’s theory, the US is in a much better place to potentially generate inflation than Japan was, particularly given recent fiscal action and proposed future fiscal action.

At Voss we have continuously noted that the US consumer balance sheet is about as good as it has ever been. Debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income has been in a downward trend since 2000.

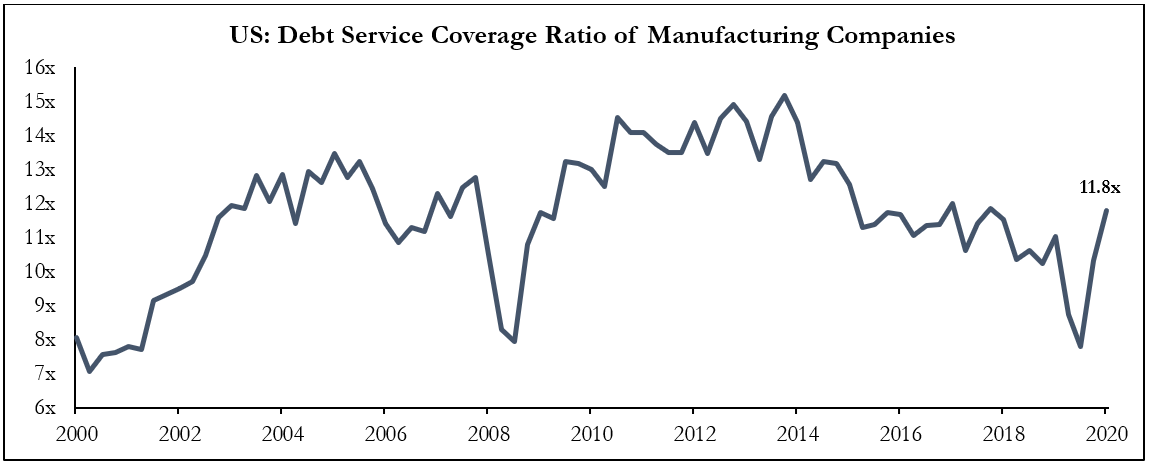

Similarly, while US corporations have more elevated debt, extremely low interest rates means their coverage ratios are quite high. For example, the US manufacturing sector is currently at 11.8x interest coverage.

Now, because of COVID, there has also been strong fiscal stimulus with the potential for much, much more if Biden’s multi-trillion infrastructure bill passes. While the bill appears to raise taxes as well, we believe Koo would conclude the net effect would still be stimulative, although the devil will be in the details as to how stimulative.

Following Koo’s logic, we conclude that with strong direct fiscal stimulus, a healthy consumer balance sheet, and a Fed willing to let inflation run above target, the United States is in a position to finally see real, sustained inflation.

The argument of why the US is “not Japan” is strengthened by a few more theoretical factors, notably that American psyche is likely nowhere near as damaged as Japan’s was following the 1990 collapse. The financial and psychological damage back then was significant and more like the Great Depression whereby an entire generation could hardly fathom the idea of taking out debt again. In fact, as we have discussed in Part I and in our quarterly levels, there are signs that Americans are starting to spend even more aggressively. For instance, there is a home buying boom underway in the US with real estate prices rocketing upwards amid an unprecedented housing supply shortage, even as builders aggressively complete housing projects. As Zillow noted in late January:

“Currently, there are fewer than three months of supply of homes on the market, the lowest on record since the turn of the century.”

Some also argue that Japan is simply financially more conservative culturally, with longer term trends of holding more cash than the United States, and that Japan may have fewer domestic investment opportunities given its highly contained geography.

Still, there is uncertainty and data points to monitor. For instance, it is hard to know if the American psyche towards taking on additional leverage could change, especially with the disruptive (potentially deflationary) effects of COVID not fully playing out economically. So far, growing deposits at banks over the past year has yet to result in any loan growth to speak of.

Second, we don’t really know how the US consumer will react to even moderate inflation. Will they begin cutting back on spending at even the slightest hint of interest rates rising? This has been an issue in Japan where any time prices begin to rise there is a quick and severe reaction to curtail spending, as this article notes:

“When prices start to rise, Mrs. Watanabe cuts spending. So firms don’t raise prices, and because they don’t want to squeeze their slim profit margins, they don’t raise wages either. Mrs. Watanabe’s income remains stagnant, so she remains hyper-sensitive to price rises. It’s a demand-deficient feedback loop that traps inflation on the floor.”

Finally, an aging population in the US may be a headwind as the older crowd becomes more conservative and wants to save more. While the US is not nearly as old as Japan, who has the oldest population in the world with 29% of the population 65 or older (compared to the world average of 9% and 16% in the United States), we are moving into the part of the curve where Japan became very sensitive to modest inflation and where savings rates remained elevated.

Takeaway

At Voss we agree that if fiscal stimulus remains aggressive, we will likely see higher, for longer inflation. There are clear differences between the US and Japan (and Western Europe for that matter) in culture, policy, and psyche. The questions are “how high” and is there a risk it gets out of control? We believe a key flaw in Koo’s analysis is that he essentially assumes that there is the capacity for unlimited fiscal stimulus. In other words, that the United States government can borrow to infinity if needed. His open scorn towards “fiscal austerity” leaves the possibility, or risk, open for more runaway inflation that might be challenging to stop once it has started. For instance, very smart people have been predicting (unsuccessfully) for years that the Yen would implode from all the QE along with a gigantic ongoing fiscal deficit. It is only several years ago that Europe faced material sovereign debt risk with Italy and Greece. Nobody can really predict when the international markets declare a country is too levered, but when it happens it can happen quickly.

So if not Japan, might the US end up like the Weimar Republic post-World War I with crippling hyperinflation? That will be the discussion in the final article in this three-part inflation series.

Richard Koo

Richard Koo

Richard Koo

Do you if the amount of consumer debt is declining? Credit Card debt has declined but I think overall consumer debt reported by Experian has increased about 6% in 2020. If the debt is increasing & we assume it is going to paid back w interest then we continue to pull more future demand forward & slow growth & inflation. In this view held by Irving Fisher & Lacy Hunt, the more debt we pile on the lower future growth & inflation will be. This is an empirical observation of over 200 years of data. Now if there is a default on the debt the you will quickly get inflation as the money supply will fill the hole left by the default.